What a Time to Be Alive

我们生活的时代

A few things going on in the world today:

世界上正发生着一些事情:

- War in Ukraine 乌克兰战争

- Global pandemic 全球大流行

- Political uncertainty 政治不稳定性

- Crashing financial markets 金融市场崩盘

- $7 gas 7 美元的汽油

- Layoffs 裁员

- Inflation 通货膨胀

And we are only two years into this century’s “Roaring 20s.” There is so much chaos in the world today that it’s easy to say “life sucks, the world sucks, and everything sucks.”

我们进入本世纪“咆哮的二十年代”只有两年的时间。当今世界如此混乱,我们很容易去说“活着糟透了,世界糟透了,一切都糟透了”。

Today, I am asking you to consider a different, more optimistic take: Life is good. In fact, it isn’t just good. Life is the best that it has ever been.

今天,我请求你用一个不同的、更乐观的视角去看待这一切:生命是美好的。事实上,它不仅仅美好。而是有史以来最好的。

Turn Back the Clock

让时钟倒转

- Death

- 死亡

If we were living in Alexandria in year 0, Kyoto during the samurai era, Stockholm in 1655, or Paris during Napoleon’s reign, each of us would have had a coin flip’s chance of surviving adolescence. Maybe we wouldn’t have survived our own births. Maybe we would have fallen victim to famine, sickness, war, infection, labor, or an abundance of other adverse conditions.

如果我们生活在亚历山大纪元0年、武士时代的京都、1655 年的斯德哥尔摩或拿破仑统治时期的巴黎,我们只有50%的可能活过青春期。也许我们不会在自己的出生中幸存下来。也许我们会成为饥荒、疾病、战争、感染、劳动或大量其他不利条件的受害者。

From 500 BC to 1900 AD, death reigned supreme. The world’s average youth mortality rate, defined as death before age 15, was 46.7%. Additionally, one-quarter of all infants didn’t reach their first birthdays.

从公元前 500 年到公元 1900 年,死亡率居高不下。世界平均青年死亡率(即15岁之前死亡)为 46.7%。此外,25%的婴儿活不过一岁。

For 2400 years, your odds of reaching your 15th birthday were reduced to the spin of a roulette wheel. But over the last century, everything changed.

在这2400年中,你活不到15岁的概率降低至轮盘博彩获胜那么低。直至上世纪,一切都改变了。

By 1950, the global youth mortality rate had nearly been cut in half to 27%. In 2017, we hit 4.6%. Somalia, which currently boasts the world’s highest youth mortality rate at 14.8%, sits at just 1/3 of the global average from ~100 years earlier.

到 1950 年,全球青年死亡率几乎降低了一半,降至 27%。 2017年,降低至4.6%。索马里目前拥有世界上最高的青年死亡率,为14.8%,与约 100 年前相比,仅占全球平均水平的 1/3。

In 2022, the death of a child is a tragic occurrence. In 1822, it was a normal part of daily life. We can’t comprehend a world where early deaths were so common, yet that was the real world for millennia.

在2022年,孩子的死亡是一件悲惨的事情。在 1822 年,这是日常生活的一部分。我们甚至无法去理解一个早逝如此普遍的世界,但那是几千年来世界的常态。

Static mortality rates for centuries, then a 90% decline in just a few generations. Insane progress.

延续了几个世纪的静态死亡率,在短短几代人中下降了90%。真的是疯狂的进步。

- Poverty

- 贫困

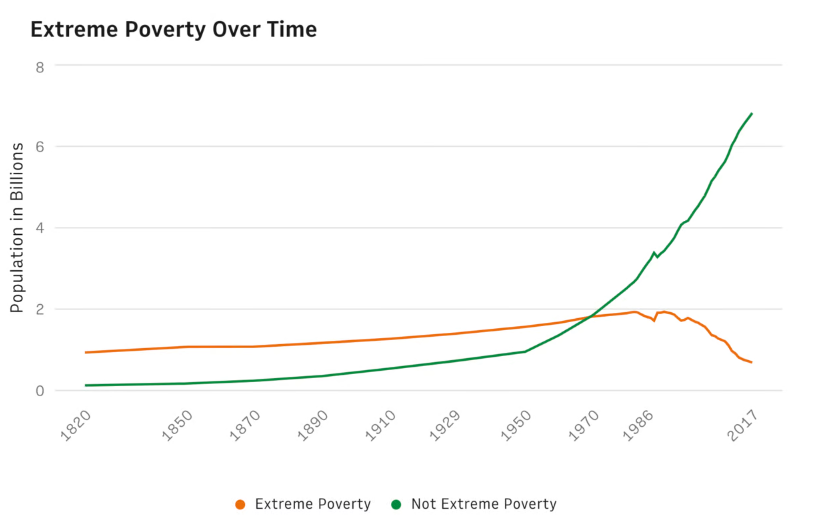

In 1820, with a global population of 1.08B, 964.93M people lived in extreme poverty (living on less than $1.90 per day in 2015, adjusted for inflation). In 2015, with a global population of 7.35B, 733.48M people lived in extreme poverty. While the world’s population increased by 6.3B, the number of people living in extreme poverty decreased by 230M.

1820 年,全球人口为10.8亿,其中9.6493 亿人生活在极端贫困中(每天的生活费不足1.90 美元,以2015年极端贫困的生活标准计算,该数字经通货膨胀率调整)。 2015年,全球人口 73.5亿,有 7.3348 亿人生活在极端贫困中。虽然世界人口增加了63亿,但生活在极端贫困中的人数却减少了2.3亿。

We often focus on wealth inequality in the US. And it’s true, the wealth gap is growing. But what gets missed in this wealth gap comparison is just how much better off poor people are now than at any point in the past.

我们常常关注美国的财富不平等。的确,贫富差距正在扩大。但是,我们在这种贫富差距比较中遗漏的信息是,现在穷人的生活比过去任何时候都好得多。

You can be “poor” in the United States today and have a cellphone, an internet connection, food, and shelter. Those living in government housing today have a higher standard of living than the upper class did in year 1900. JD Rockefeller, the richest man in modern history, didn’t even have air conditioning.

今天,你在美国可能是“穷人”,但是仍然拥有手机、互联网连接、食物和住所。现在住在政府住房的人的生活水平比1900年的上层阶级都要高。当代历史上最富有的人戴维·洛克菲勒甚至都没有空调。

As recently as 1981 (!!!) 42% of the world lived in extreme poverty. Today, that number is just 9%. In the last generation, global extreme poverty has dropped by 84%.

就在 1981 年(!!!)世界上还有 42% 的人生活在极端贫困中。今天,这个数字只有 9%。就在上一代人中,全球极端贫困人口减少了 84%。

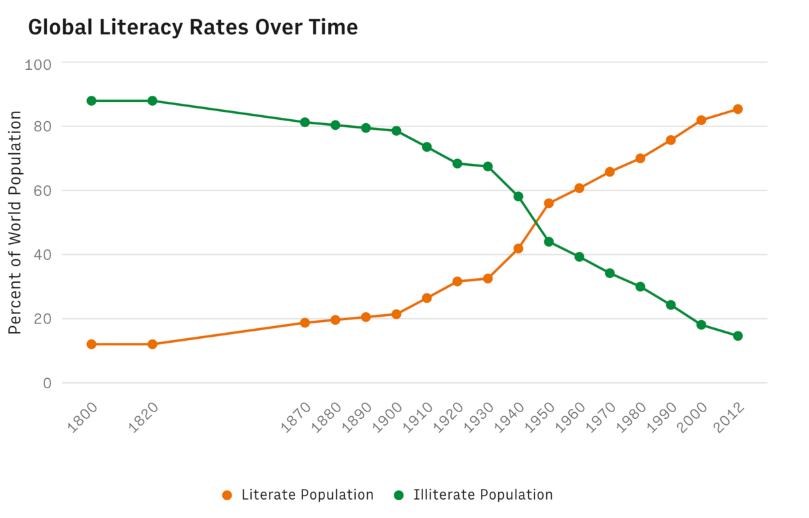

A variable highly correlated to poverty? Literacy.

一个与贫困高度相关的变量?认字。

- Literacy

- 认字

Even centuries after the advent of the printing press, books were still reserved for the elites. Written knowledge passed down from generation to generation could only be accessed by a select few, with the rest of the populace relying on word-of-mouth communication. Letters couldn’t be written. Notes couldn’t be taken. Information couldn’t be recorded, unless you were born into the right house.

即使在印刷机出现的几个世纪后,书籍仍然是为精英们使用的。代代相传的书面知识只能由少数人获得,其余民众则依靠口耳相传。无法写信。无法记笔记。除非您出生在精英家族之中,否则无法去记录信息。

In year 1800, just 12% of the world’s population was literate.

In year 1900, just 21% of the world’s population was literate.

In year 2016, an astounding 86% of the world’s population was literate.

1800 年,世界人口中只有 12% 的人识字。

1900 年,世界人口中只有 21% 的人识字。

2016 年,惊人的是,86% 的世界人口识字。

- Perspective

- 视角

If you were born in Paris, France in 1820, you had a 56% chance of making it to your 15th birthday. Assuming you survived, there was a 38% chance that you knew how to read and write. And even if you were alive and literate, (a combination with just a 21% chance of happening), you had a 50/50 shot of being in extreme poverty.

如果你在1820 年出生于法国巴黎,你拥有 56% 的机会活到 15 岁的生日。假设你幸存下来,你有 38% 的机会知道如何阅读和写作。即便你还活着且有文化(这种组合的概率只有 21% 的机会发生),你也有50%的几率处于极端贫困中。

But let’s say that you beat the odds. You were a living, literate Parisian with a modest income. Welcome to the good life.

但是,假设你战胜了困难。你是一个活着的、有文化的巴黎人,有着微薄的收入。那么,欢迎你来到精彩的生活部分。

You would have spent your entire adulthood in a chaotic, politically unstable post-Napoleon France. Your grandchildren would have fought in WW1, and their children would have fought in WW2.

你会在后拿破仑时代的一个混乱、政治不稳定的法国度过整个成年。你的孙子会在第一次世界大战中战斗,他们的孩子又会在第二次世界大战中战斗。

The reward for overcoming all of life’s obstacles was two generations of war that tore your country apart.

克服生活中所有障碍的回报则是两代战争撕裂了你的国家。

But at least gas wasn’t $7 per gallon.

但至少汽油不是每加仑 7 美元。

It’s hard to internalize just how good we have it because our own life experiences are our homeostasis, our base point for comparison. We read about the hardships of history, but we don’t experience them. We don’t feel them. How could we? Decades of war, sickness, and hardship have been reduced to paragraphs and documentaries.

我们很难去把这部分进行内在化处理,因为我们自己的生活体验是我们内在的平衡点,我们比较的基点。我们读到了历史的艰辛,但我们没有经历过。 我们感觉不到它们。 我们怎么可能去体验它们?数十年的战争、疾病和困苦已被简化为段落和纪录片。

But those wars, sicknesses, and hardships were all-too-real for those who lived through them.

The Plague of Justinian wiped out 40% of Constantinople’s population in four months. The Russian Plague killed 33% of Moscow’s population in a single season, and 75% of the remaining populace fled.

查士丁尼瘟疫在四个月内消灭了君士坦丁堡 40% 的人口。俄罗斯瘟疫在一个季度的时间杀死了莫斯科 33% 的人口,剩余人口的75%逃离了莫斯科。

The Covid-19 pandemic has been bad, no doubt. But can you imagine a world with 4M New York City deaths in just four months? Where millions of others flee, fearing for their lives?

毫无疑问,Covid-19 大流行很糟糕。 但是你能想象这样一个世界,短短四个月内有400 万纽约市人口死亡吗?还有数以百万计的其他人逃离,因为担心他们的生命安全?

Because that happened. And it happened more than once.

这样的事情确实发生过。而且它发生了不止一次。

These accounts feel like faraway stories from an era in the distant past. Lost somewhere between fact and fantasy. But they were just as real to the past generations as our conflicts are to us today.

这些叙述感觉像是来自远古时代的遥远故事。 迷失在事实和幻想之间。 但它们对过去几代人来说,就像我们现在经历的冲突对我们那般的真实。

- A Million Little Miracles

- 一百万个小奇迹

History is nothing if not a series of mankind conquering nature’s limitations.

如果不是一群又一群的人类战胜了自然的极限,那么历史就不会成为历史。

The printing press allowed our knowledge to conquer death.

印刷机让我们的知识战胜了死亡。

Penicillin allowed our bodies to conquer infection.

青霉素让我们的身体战胜了感染。

Fertilizers allowed our farms to conquer famine.

肥料让我们的农场战胜了饥荒。

Steam engines allowed our ships to conquer windless seas.

蒸汽机使我们的船只能够征服无风的海洋。

Airplanes allowed us to conquer gravity and distant travel.

飞机使我们能够克服重力和遥远的旅行。

Phones allowed us to conquer long-distance communication.

电话使我们能够征服长距离通信。

Computers allowed us to conquer the spatial limitations of data storage.

计算机使我们能够克服数据存储的空间限制。

Over time, these little miracles, these little breakthroughs, they compounded. Each generation built from the shoulders of their predecessors, beginning life on third base thanks to a triple hit by the generation before.

随着时间的推移,这些小奇迹、小突破,它们会变得更加复杂。每一代人都建立在前人的肩膀上,继续开创新的生活。

And innovation has accelerated as a result.

因此,创新加速了。

Every single thing that we take for granted today would be nothing short of a miracle to anyone who lived just 100 years ago.

对于生活在 100 年前的任何人来说,今天的我们所体验的任何一件理所当然事都是奇迹。

Supermarkets with fresh selections of every food imaginable are magic. Planes that will transport you anywhere in the world in under a day are magic. Clean water is magic. Antibiotics are magic. Cell phones are magic. Plumbing systems are magic. Anesthesia is magic. The fact that you can read this blog from New York, to New Delhi, to New Zealand is magic.

超市里拥有着可以想象的任何一种新鲜的食材,这很神奇。在一天之中,你可以乘坐飞机到达世界各地,这很神奇。有着干净的水源,这很神奇。抗生素的存在,也很神奇。智能手机很神奇,管道系统很神奇,麻醉术很神奇。不论你在纽约、新德里、还是新西兰,都能阅读这篇博文,很神奇。

But to us, none of this is magic. To us, the real magic is that our ancestors survived with so much less.

但是对于我们来说,这些都不神奇。对我们来说,真正的奇迹是,我们的祖先拥有那么少,仍然存活了下来。

Inflation sucks. Covid sucks. War sucks. High gas prices suck.

通货膨胀很糟糕。 冠状病毒很糟糕。 战争很糟糕。 高昂的汽油价格很糟糕。

But we live in a world where you can Facetime your best friend from another country, and they can fly to visit you the next day. You can instantly communicate with anyone who has an internet connection. The poorest people in first-world countries still have food, water, shelter, and access to healthcare, while 200 years ago a large gash on your leg was a death sentence.

但是我们生活在这样一个世界,你可以与来自任何国家的好朋友进行视频聊天,他们也可以在第二天乘坐飞机来拜访你。 你可以即刻与任何拥有互联网连接的人进行交流。 居住在世界上最贫困的国家里的人仍然有食物、水、住所和医疗保健,而在 200 年前,你腿上的一条大伤口,就对你宣判了死刑。

We struggle with purpose, our ancestors struggled with survival.

我们为目标而奋斗,我们的祖先为生存而奋斗。

Asking “What do I want to do with my life?” is a privilege, considering the primary concern for everyone before us was “How do I stay alive?“

提出 “我想用我的生命来完成什么?” 这样的问题是一种特权,我们之前每个人的主要关注点是“我要怎样活下去?”

So while we tweet, text, and opine about the disastrous state of the world today, it is important to remember that the depths of our modern hells would be the pinnacles of our ancestors’ lives. Our problems are a privilege.

因此,当我们在发信息、短信和网上评论当今世界的面临的灾难时,重要的是记住,我们现在所处的炼狱深处,是我们祖先生命的巅峰。我们面临的问题,都是一种特权般的存在。

原文:https://www.youngmoney.co/p/time-alive

翻译:Soluna